Convoy Duty

Convoy is the practice of transporting men or material together for the purpose of safeguarding them. Although most famously used as a means to counter the U-boat menace in the two world wars, it has long meant the grouping together of military as well as civilian ships or vehicles for control as well as protection. During the medieval period ships sailed in concert for mutual protection but the use of an organized convoy system as we now know it dates from the separation of ships into specialist classes and the development of a state-based navy.

During the Anglo-Dutch wars of the 17th century merchantmen were regularly organized into escorted convoys along trade routes dictated by the prevailing winds. These protected them from individual raiders but not from fleet actions and in 1665 a Dutch convoy had its escort overwhelmed and 180 out of 200 merchantmen taken. In spite of events like this, insurance premiums on vessels in time of war were consistently lower for those that sailed in convoys. By the time of Waterloo the Royal Navy had in place a sophisticated system for the protection of merchant ships. Early in the conquest of America, Spain employed close escorts and support forces to safeguard its homeward-bound treasure galleons. It established a compulsory convoy system in 1543, enabling the merchants of Seville to dispatch a flota ("fleet") of thirty to ninety merchantmen twice annually to the West Indies, thereby frustrating repeated attacks by British and French freebooters. The Armada of 1588 itself represented a classic prefigurement of the modern troop convoy.

Subsequent English overseas expansion rested not only on mercantile enterprise, an emergent Royal Navy, and deliberate nurture of the colonial system through the Navigation Acts, but also on resolute enforcement of the convoy acts, dating from 1650, that regulated the organization of convoys and required the arming of merchantmen. Throughout its conflict with France from 1674 to 1815, England refined, notably in the Compulsory Convoy Act of 1798,the complex operation of its ocean and coastal convoy systems. During the American Quasi-War with France , U.S. frigates escorted British convoys in the Caribbean; less than fifteen years later those frigates, abetted by privateers, attacked British transatlantic convoys with but limited success.

With the coming of steam it was argued that since ships could now move independently of the wind, they could avoid interception altogether. The "all your eggs in one basket" argument was put forward, as were the arguments that convoys would clog up ports, delays would occur due to ships waiting for the convoy to form up, and anyway there were too many ships to convoy. Behind these arguments was a deeply felt belief that submarines could be hunted like any other warship and that convoys were somehow effeminate, a position to which the Admiralty clung despite abundant proof to the contrary until obliged by Lloyd George to reintroduce convoys in 1917.

This same psychopathology afflicted the US Navy's Adm King in 1941-2, when he ignored bitterly won British experience and opposed the introduction of convoys in American waters, being therefore personally responsible for the loss of hundreds of merchant ships and thousands of lives. The Japanese refused to adopt the convoy system throughout WW II and lost their entire merchant navy. The British found that convoys, by enabling escort vessels to be concentrated, became the focus for hunter-killer operations with which they inflicted greater casualties on the U-boat service than suffered by any other branch of any country's armed forces. Convoys were still vulnerable to heavy German surface raiders, but with the exception of the infamous scattering of the Arctic convoy PQ 17, escort vessels self-sacrificially defended their charges against this threat also. The "all your eggs in one basket" argument acquired renewed vitality in the age of nuclear attack submarines and stand-off weapons that could deliver tactical nuclear weapons. Happily the matter was never put to the test.

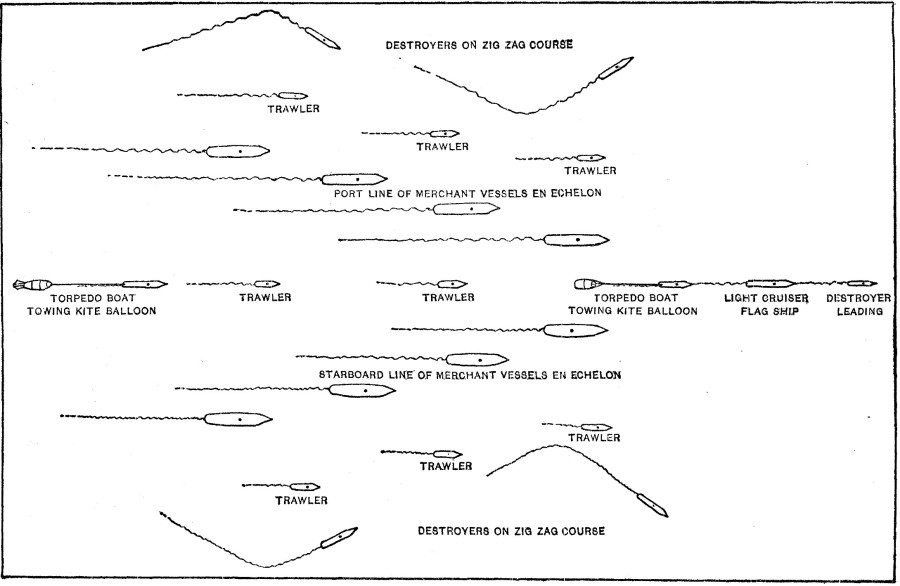

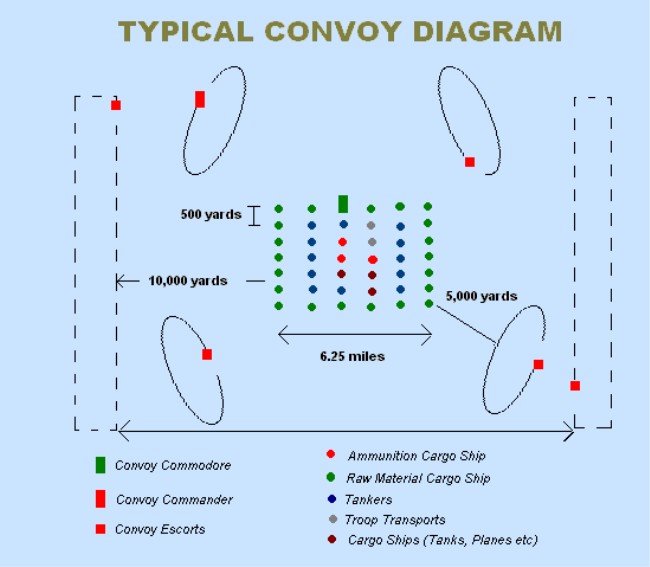

In World War I the British organized transatlantic convoys protected by a cordon of warships; the same system protected Allied shipping from German submarines during the Battle of the Atlantic in World War II. During the Iran-Iraq War, oil tankers transiting the Strait of Hormuz into and out of the Persian Gulf were escorted by warships of the U.S. and other Western navies. With the establishment of the Pax Britannica, the vital role of convoys rapidly diminished. Notwithstanding the virtual disintegration of the American merchant marine during the Civil War, the British Admiralty in 1872 acquiesced in abolishing the Compulsory Convoy Act, relying thereafter on naval patrol of threatened sea routes. That policy proved disastrously ineffective during World War I against commerce-raiding German U-boats. Not until May 1917, when shipping losses threatened Britain with imminent starvation and U.S. escort vessels became available, did the Admiralty reinstitute convoys.

The vast shipping control system that developed, with its complex intelligence apparatus, decisively reduced losses of merchant ships bound for Britain and safeguarded the massive American troop movements to France. Allied convoy systems during World War II achieved worldwide dimensions, owing to the phenomenal range of Germany's commerce-raiding effort, which included a substantial Luftwaffe threat in the North Sea, the Arctic, and the Mediterranean. The Allies virtually eliminated Germany's surface raiders during 1943, but German U-boats, operating singly or in "wolf packs" of fifty or more submarines, extended "tonnage warfare" strategy from the North Atlantic to the Caribbean, the South Atlantic, and ultimately the Indian Ocean. Allied experience indicated both the suicidal impracticality of independent merchantman sailings and the striking economy of large convoy formations, particularly as land and carrier-based air cover, pinpoint location of individual stalkers by radar and high-frequency direction finders, and evasive convoy-routing procedures increasingly hampered U-boat reconnaissance patrolling. With the advent of nuclear weaponry, the wide dispersion of convoyed shipping, and the employment of aerial transports, as during the Berlin Airlift, became characteristic elements of modern convoy operations.

Bluejacket

Bluejacket